[Rec] 2 (Released 28th May 2010 in the UK)

Directed by Jaume Balaguero & Paca Plaza

Every once in a while, a film comes along that strikes a chord with the audience, whether it is through word of mouth, clever marketing, marking a new step with the evolution of technologies or otherwise. In 2008, a Spanish film about a reporter following the routine of a fire crew in Barcelona terrified audiences enough that Hollywood remade it as Quarantine within a year of it hitting the screens. That film was [Rec].

It utilised the same technique that had garnered Cloverfield (2008) so much attention, that of events unfolding before a first person viewpoint. In Cloverfield the camera operator was named Hud, (an acronym for Heads Up Display) but where Cloverfield covered a city under attack by an unknown entity, [Rec] drew more upon the fear of being in an unfamiliar place where something unexplainable is happening before the operator and by proxy the audience’s eyes.

The final shot of [Rec] is where [Rec] 2 takes over.

The reporter who has discovered a creature in the attic of the apartment complex is dragged into the darkness, her fate unknown, the camera filming only black. Instead, the film cuts to a specialised police force en route to the complex, knowing little about what has happened except that the governing body wishes to have video documentation of the events.

The abiding “rules” of a horror sequel are in effect here; more story development, more action and more monsters. These boxes are all bloodily ticked off.

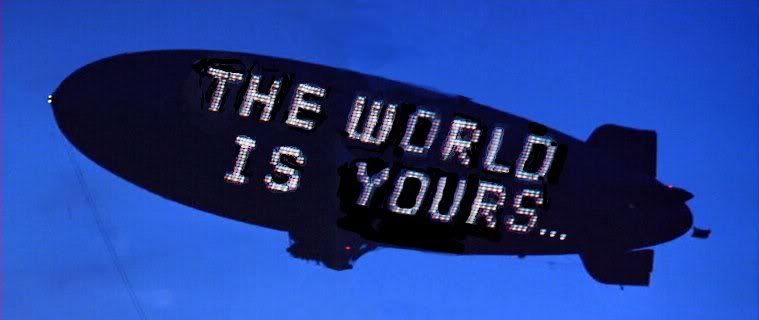

Where the original followed one group as their numbers steadily dwindled, [Rec] 2 splits the film between the police and a group of teenagers who, curious with the commotion outside the building, decide to sneak in armed only with the arrogance of youth and a camcorder of their own. In the age of YouTube phenomenon’s and people documenting their own lives, the teenagers’ dreams of fame (“This is our chance!” screams one) quickly turn into a nightmare they cannot escape.

Further expanding on the single camera concept of the original, the police force have miniature cameras on their helmets and guns, capitalising on the burgeoning first person shooter computer games. However in games of this type, the person is in complete control. In [Rec] 2 the viewer cannot escape; they are trapped not only in the overall situation but trapped also by the choices the characters make. The directors incorporate some post-production effects to enhance the experience; the battery power display would not be visible but adds to the tension and in one attack, the camera freezes on a horrific image, with the zombie screech distorted also.

The film is by no means without its flaws. The search for test tubes of blood from which to create an antidote is laboured and dragged out; tension rapidly turning into frustration as one tube goes up in flames in an unintended farcical fashion. While the revelation of a ‘health inspector’ actually being a priest appears in the trailer, when seen in the film, the reveal seems to be more at home in a B-movie; he removes his luminescent jacket to show his dog collar underneath, bearing resemblance to Clark Kent undressing before Superman takes flight.

Even prior to [Rec], the concept of a zombie outbreak being documented via camera had been used in George Romero’s Diary of the Dead (2007) but it would be unfair to accuse the directors of simply just “cashing in” on a gimmick. The alteration the [Rec] films offer to the zombie sub-genre goes beyond the hand-held camera, these zombies are also possessed. Perhaps this altering of the conventional zombie means more to the home Spanish market than the foreign markets, as a poll undertaken in 2010 showed 75% of the population identify themselves as Roman Catholic.

The idea of an inner demon being awoken and able to possess different bodies at will is unlikely to translate as well to more secularized cultures, but fits well with the Spanish culture.Despite having a running time of only 85 minutes, once the opening half hour zips past the film-makers seem to be caught in two minds between trying to keep up the frenetic pace or pause and allow their characters to catch their breath. This results in a continuing stop-start pacing for the remainder of the film until the final fifteen minutes where the focus is solely on tension and suspense that sets up the 3rd installment quite nicely.

By no means an Aliens (1986) or an Empire Strikes Back (1980), but a solid enough effort that does no harm to the first and a worthy addition to the evolution of the zombie horror sub-genre.

Overall Rating - B-

Word Count -789